Eighth-day coverage of the 68th Berlin International Film Festival with reviews of the Iranian comedy Pig (Khook) and the Brazilian documentary The Trial (O Processo)

Pig (Khook)

In Mani Haghighi’s Pig, filmmakers in Iran are being targeted one by one by a mysterious serial killer who chops their heads off and uses a razor to carve the word “Khook” (or “Pig,” in Persian) on their foreheads. So, one might wonder, is this a political commentary on Islamic censorship in Iran disguised as a thriller? Well, no. In fact, this is a comedy that has no other pretension than just being funny. Now, if it’s unpretentious or simply witless, that’s another story.

The film is centered on a blacklisted director, Hasan (Hasan Majuni), who hasn’t been allowed to shoot a film in years and is now working on a pesticide commercial. He is furious that the actress and muse he turned into a star, Shiva (Leila Hatami), is bored of being idle and wants to work with other directors. He is obsessed with her, and to make things worse, he and his wife have been drifting apart, his old mother is losing her mind, and there is a serial killer at loose in Tehran. Hasan doesn’t understand why the killer is not targeting him, of all directors. But, of course, it won’t take long for him to become the prime suspect.

With the kind of slapstick humor that invests in a lot of fast cuts and people screaming after seeing a dead body, Pig wants to make fun of its unkempt protagonist but ends up making him too immature and hard to care about. Hasan is a douchebag who treats Shiva like a property, forbidding her to work with other filmmakers and always blaming her for his emotional stress (“What have you done to me?” he asks her in one of his macho fits). Someone even mockingly refers to him as “her master,” and he is impulsive enough to go around yelling that he will kill her only to become a suspect later.

And while it’s infuriating that Shiva is so passive and complies with his possessive demands (leading to a pathetic moment when Hasan sees fireworks because she finally gave in), the film includes baffling situations that make no difference for the narrative, like when he is stung by a bee or hallucinates that he is playing a neon tennis racket like a guitar, in a pointless, flashy and tiring musical number full of superfast cuts. Besides, more stupid than the police missing the killer after being distracted by Hasan’s “pronounced image” on a surveillance video is only his plan to catch the killer, which makes no sense and whose outcome we can see from miles away.

But what is frustrating is that there are elements here that could have led to a better film. At some point, Hassan tells a director they should stop making films to protest (“Think how History will judge us”), but that doesn’t go anywhere. Later, the film talks about unfounded accusations that go viral allowing everyone to have “an opinion.” There is a nice criticism on our YouTube/Twitter/Instagram generation lost in a harmless film that cannot find anything relevant to say, not even when revealing the identity of the killer. So if Haghighi only wanted to make a witless, vapid comedy, then mission accomplished.

The Trial (O Processo)

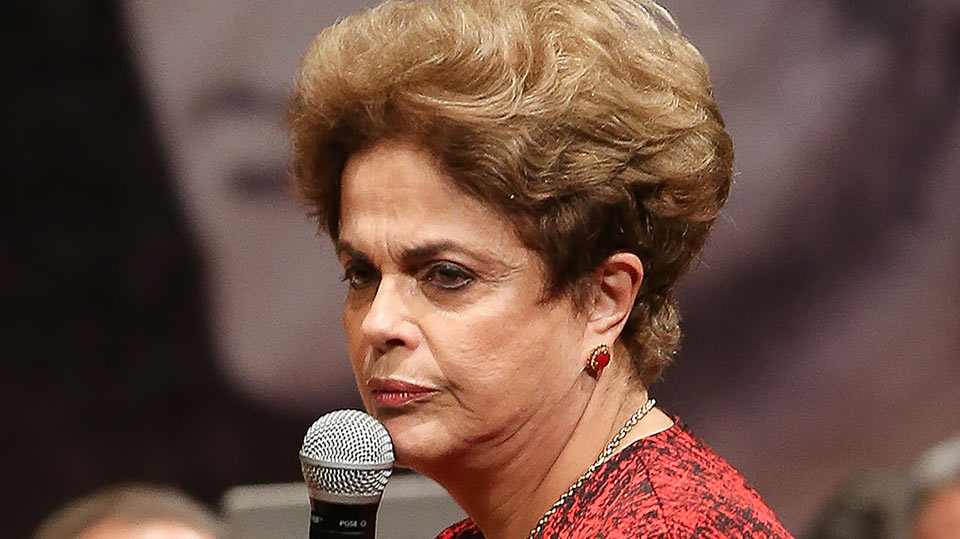

While attending a Berlinale screening of the documentary The Trial, the general feeling among the Brazilians that were there (most of the audience, I presume) was collective desolation. The reception to Maria Augusta Ramos’s film was extremely positive, with lots of clapping and praise from the audience during the Q&A, and there was a shared understanding in the air. Ever since a parliamentary coup (with full support of a rotten media) impeached President Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and replaced her with Vice President Michel Temer (who in turn was accused of corruption), Brazil is no longer a democracy, and we know it.

Ramos told us she began shooting her film 10 days before the initial Congress vote, and while she didn’t gain access to the Chamber of Deputies where the impeachment process began (the images we see from there are public material), she was allowed to film at the Federal Senate after the Chamber voted in favor of the impeachment and the motion passed. In the end, she had an unbelievable amount of 450 hours of material which finally got edited down to a concise 137 minutes. Aiming at a wholly observational, fly-on-the-wall approach, the result is an authentic courtroom drama presented without any narration or exclusive interviews. With so much being said on both sides of the trial, there is no need for commentary.

The Trial details each step of the impeachment process, beginning with Rousseff accused at the Chamber of Deputies of criminal administrative misconduct after no evidence had been found implicating her in a corruption scandal at Brazilian national oil company Petrobras (of whose board of directors she was president). The charges included “fiscal pedaling” — an accounting maneuver which had been used by previous Presidents and involves delaying repayment from the Treasury to state-owned banks used to pay government obligations — and the signing of six budget decrees to allocate funds to social programs without authorization from Congress. That is, basically technicalities, since these measures didn’t lead to an actual financial loss.

In only a few initial scenes, Ramos’s film exposes how this trial was a circus from the beginning, with the Chamber being presided by a criminal, Eduardo Cunha (who was under investigation for corruption) and agitated deputies yelling insanities about God, the police and the military during their open vote — including a fascist deputy exalting a torturer and a woman who had the nerve to justify her vote in favor of the impeachment as being “for all those who fought against the military dictatorship.” We soon realize the Chamber committee had the power to reach whatever conclusion they wanted, and that the outcome of this trial had been decided right from the start, whether there was just cause for impeachment or not.

As the motion passes to the Senate, the film lets us participate in the meetings and strategies of Rousseff’s defense team, whose carefully studied arguments are met with absurd decisions by the investigative committee. And while prosecution lawyer Janaína Paschoal seems more like a bizarre lunatic who claims in tears that she is in love with the Federal Constitution, one senator even admits he doesn’t know if there was crime but insists that Rousseff lies anyway. The trial reaches moments of such absurdity that the film’s title (a reference to Franz Kafka’s The Trial) couldn’t be more appropriate, since someone is also convicted here for a crime that makes no sense and no one can exactly explain what it was.

But the reasons behind this prosecution can be found in a few revealing scenes, like when we see the well-off middle class celebrating the impeachment in the streets in contrast with those from lower classes suffering in silence for Rousseff. In other words, Ramos’s film clearly argues that this is a woman who dared to defy the interests of a small group of powerful men and paid the price for it. Of course, there will be people “accusing” it of being one-sided, but it takes only one look at the fact that the Congress voted not to put Temer on trial to realize that this was never a fair process, but pure retaliation and opportunism.