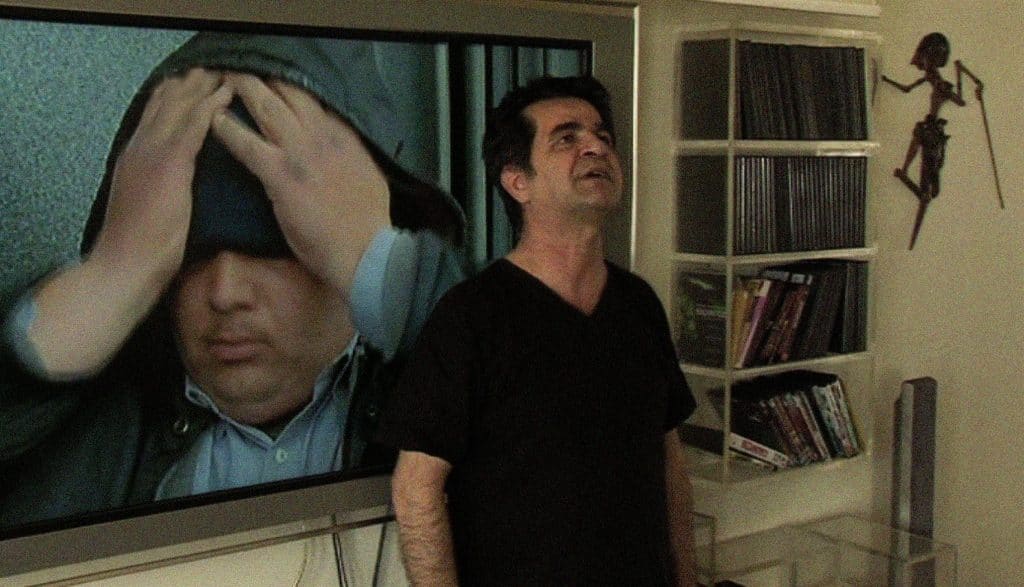

Under house arrest, Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi creates a powerful humanist manifesto against censorship and lack of freedom of speech in his country

This Is Not a Film (In film nist) (2011)

Directed by Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb.

In 2010, Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi was arrested by the government and taken by fifteen plainclothes officers from his home along with his wife, daughter and fifteen guests — including prominent filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof — to Evin Prison in northwestern Tehran, a place nicknamed “Evin University” for housing a great number of intellectuals and political prisoners. Panahi has always been an outspoken supporter of the opposition and because of that was convicted for “assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic.” The Islamic Revolutionary Court then sentenced Panahi to six years of imprisonment with a 20-year ban on making films, writing screenplays, leaving the country and giving interviews.

Under house arrest while awaiting the result of his appeal, Panahi decides to document his life and begins to film himself in his apartment. We see him having breakfast in front of his camcorder and later talking on the phone with his lawyer, who acknowledges that the court rulings are 100% political and not at all legal, and that it could be possible to lift the ban and reduce his sentence, even if imprisonment is a certainty. Panahi calls his friend and fellow filmmaker Mojtaba Mirtahmasb and asks him to come and help him document the film he was planning to make before his arrest. He tells Mirtahmasb to make sure that no one knows he is coming, for fear of what might happen. There is a whole secretive mood since they know what they are doing is dangerous and there could be terrible consequences if they got caught.

Once Mirtahmasb arrives there, Panahi is feeling inspired by his own films to make a “behind the scenes of Iranian filmmakers not making films,” as Mirtahmasb puts it. It is great to see the two directors deciding how to proceed, first with respect to technical matters (such as any need for additional light or the level of overexposure) and then how to elaborate the geographic conditions inside the apartment so that Panahi can narrate the screenplay that he wrote but was refused (like other previous ones) by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Panahi recreates the set in his living room and explains to the camera in details how he planned to make a film that never was and probably never will be — and this should be fascinating to anyone who loves Cinema and is interested in having a peek into an artist’s creative process.

If there is something that Cinema has proven many times, it is that it can be a door to infinite possibilities, and even though we are not watching the actual film that Panahi had in mind when he wrote his screenplay, This Is Not a Film ends up offering a lot more by showing us the making of an unmade film and its implications — especially concerning the nearly nonexistent freedom of speech that an artist is allowed to have in a country dominated by religious values. This Is Not a Film is definitely a film, and it is revealing to see Panahi question himself and what they are doing by admitting that “if we could tell a film, then why make a film?” Moments like this elevate the project to something also human, while at the same time calling into question what makes a true narrative (“I feel what we are doing here is also a lie,” he says).

At some point, it is beautiful to notice that Mirtahmasb’s presence becomes almost invisible behind the camera, as Panahi is allowed to talk freely about his ideas and even how he doesn’t want to put his colleagues in trouble after 12 prominent filmmakers made an appeal for his release. In other moments, we see Panahi “alone” in the company of his lizard, the camera showing his daily life inside his apartment as he is forbidden to leave. It can be unnerving to think that his apartment has become a prison and that he cannot express his own art anymore for as long as he is in there, and this feel is intensified by the scary sounds of police sirens and what seems to be gunshots mixed with the explosions of fireworks outside (marking the Iranian festival Chaharshanbe Suri that precedes the Persian new year, Nouruz).

But This Is Not a Film (whose title is a reference to René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images) reaches the point of near perfection when Panahi leaves his apartment and has an elevator trip with a guy (an Arts research student) who collects the garbage in the building. First filming with an iPhone, Panahi then switches to his camcorder and the two have a casual talk about the guy’s life and plans for his future as the elevator goes down from floor to floor and the guy collects the trash from each apartment. It is a truly delightful moment showing common people that brings to mind the best films of Brazilian filmmaker Eduardo Coutinho in its human simplicity and humor — and I also love another light moment when Mirtahmasb makes an improvised tripod for the camcorder using a lighter and a pack of cigarettes.

Sometimes the best films are born when we least expect them, and This Is Not a Film (which was smuggled from Iran to the Cannes Film Festival in a flash drive hidden inside a birthday cake) is a fantastic example of that. Dedicated to Iranian filmmakers and making a powerful statement even in its final credits, this is a film that shows how important it is to continue fighting. Even if you can’t film, use your phone. But silence should never be an option.