A must-see eight-hour documentary that probes into an American crime and the cultural and social causes that made this shocking case possible

O.J.: Made in America (2016)

Directed by Ezra Edelman.

Orenthal James “O.J.” Simpson was a man who had everything. Handsome, charming, one-of-a-kind athlete and seemingly perfect in everything he did (like football, running or bowling), O.J. was an instant national star loved by everyone. Wherever he went, no one saw him as a black man. O.J. was so popular and adored by the public that he “transcended race and color,” as someone points out at a certain moment in this gripping eight-hour crime dossier that wants to dissect the cultural and social conditions that helped engender this Frankenstein monster in American society — and what it exposes is so shocking and unbelievable (at least for those who don’t know so well the details about what happened) that, had this real story been scripted, the writer would be considered a genius.

Directed by Ezra Edelman for ESPN Films and their excellent 30 for 30 series, O.J.: Made in America has the most appropriate title anyone could come up with. Comprehensive and thorough, the documentary uses a great number of interviews and archive footage to show O.J.’s life from his early years as an emerging football sensation at the University of Southern California to being accused of double murder, acquitted and imprisoned for another crime 13 years later. As it does so, it probes into the very ugly mold (racial oppression, hatred, celebrity obsession, sensationalism, etc.) that made this sort of ironic tragedy possible. It was by all means an American crime — and O.J., the offspring of a social cancer whose tentacles seemed to spread in many different directions.

Back in the 1960s, while O.J. was being seduced by white society in Los Angeles and everyone seemed to care only about the games, police brutality against black people in the city led to major clashes, reaching a climax with the Watts riots in 1965. “Why were they rioting?!” white people asked, baffled and completely blind to the police abuse and racism that took place right under their privileged noses. That event was then followed by black elite athletes boycotting the 1968 Summer Olympics and Tommie Smith and John Carlos being banned from the games for raising a black-gloved fist on the podium in solidarity with the Black Freedom Movement. O.J., on the other hand, always remained apolitical. “I’m not black, I’m O.J.,” he once said, aware that if you are a celebrity in L.A., you have no color.

Narcissistic and self-assured, O.J. was spoiled by his own delusions of grandeur and clearly believed himself to be above the system and the laws. O.J.: Made in America understands that and draws a fascinating profile of the man behind the myth. Known as “The Juice” (a synonym for electricity and a play on “O.J.,” which is also an abbreviation of “orange juice”), O.J. beat the record of 2,000 yards in the 1970s and was a pioneer on TV, opening the door for other black people to appear in the medium. He then quickly became a Chevrolet model and starred in commercials for car rental company Hertz, believing he could make everyone see him as a white equal (someone even says that he “almost has white features”). And he starred in movies too, like The Towering Inferno (1974) and The Naked Gun (1988), “so what could have possibly gone wrong?” the film seems to ask.

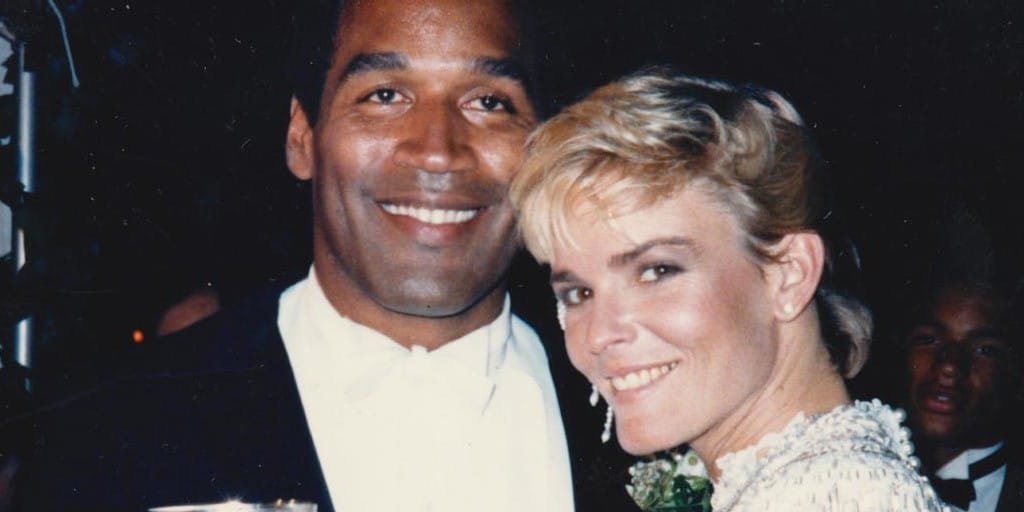

Edelman examines how O.J.’s freedom when living in the safe (and very white) Brentwood, LA made him so spoiled that no one would say no to him — and his friends would even let him cheat when playing golf. He did everything he wanted, so if someone with preferential treatment can’t meet all his needs, frustration is inevitable. After marrying Nicole Brown (whom he seemed to think of as his beautiful white prize), O.J. became jealous, dangerous and monstrously abusive. Meanwhile, another type of brutal abuse was taking place in the country: African-American taxi driver Rodney King got beaten up by the police; 15-year-old black girl Latasha Harlins was shot in the head and killed by a female South-Korean store owner (who got released); and white people were oblivious (as always) to why black people would want to burn down a community that was clearly not theirs.

In fact, if there is a flaw in O.J.: Made in America, it is the way the film tries to construct a parallel between those two types of abuse. Not that it doesn’t make sense; on the contrary, they are intimately related. The problem is that the sudden jumps back and forth between them interrupts the flow of information sometimes and makes the documentary feel a bit jumpy. But this is a minor thing. Once we get to the murders and trials, the documentary becomes considerably more focused and presents consistent arguments to support an undeniable link between racism in America and how a murderer could be set free by a jury of his peers even when every single evidence against him was overwhelming. O.J.: Made in America is therefore a complex examination of both celebrity narcissism and racial inequality in America.

For the great irony in all of this is how the prosecutors’ search for impartial jurors led to a jury composed of mostly African Americans — among them eight women and a secret member of the Black Panthers who raised his fist in court. And how a rich black man (who always hated the fact he was black) got released as payback for the way black people have always been treated in America. And, of course, how a civil trial and a case of supposedly stolen memorabilia gave white people the best excuse to throw him in jail even if this time he didn’t do anything to deserve such a harsh verdict — and the recurrence of the number 33 was, if not a suggestion of revenge conspiracy, at least a clear indicator of the irony it entailed.

In short, this was basically a classic case of white people employing injustice (or, should I say, “white justice in America”) to obtain payback against African Americans, who were rejoicing in their outspoken use of dishonesty as an act of revenge against white people in the first place (“now you know how it feels,” we hear someone say) — that is, white people who have perpetuated racial inequality in the country for centuries. It is an endless, vicious cycle, and the fact that Edelman understands the full implications of that makes his film even more astute.

Using disturbing crime images and an expert sound design to illustrate the sounds of the stabbings, for instance, O.J.: Made in America is complete as a criminal dossier, presenting so many details and circumstances surrounding the case that it feels like an ultimate documentary about O.J. Simpson (to be watched back-to-back with The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story (2016)). And what it presents is so bizarre (as a character study) and essential (from a social perspective) that it must be seen to be believed.