Darren Aronofsky creates a brilliant ecological metaphor on Christianity that could only divide its audience, fascinating some while enraging others

mother! (2017)

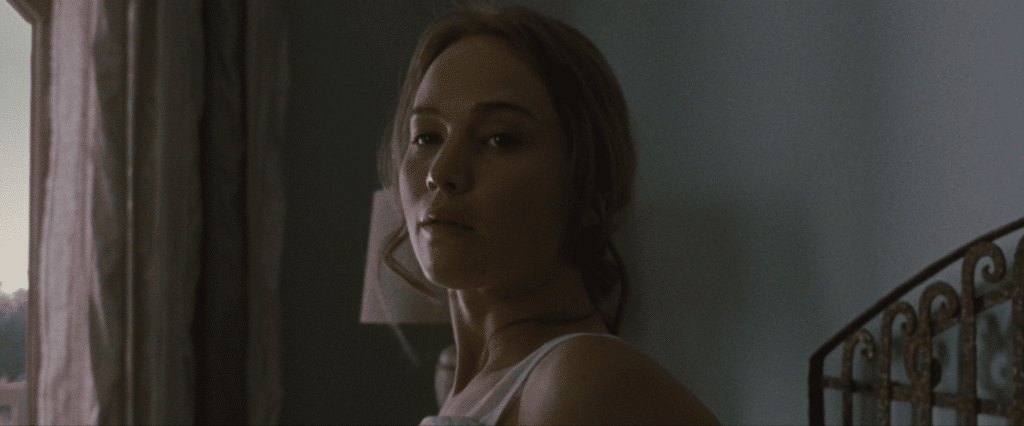

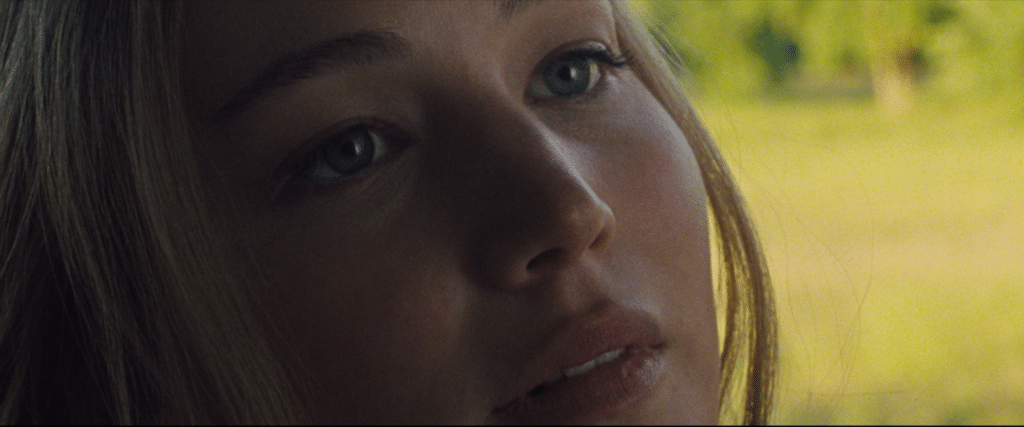

Written and directed by Darren Aronofsky. Starring Jennifer Lawrence, Javier Bardem, Ed Harris, Michelle Pfeiffer, Domhnall Gleeson, Brian Gleeson, Kristen Wiig, Jovan Adepo, Stephen McHattie and Laurence Leboeuf.

One of the things I love about Cinema is its endless capacity to provoke us. Just take a look at Darren Aronofsky’s films, for example, and you will find some fascinating symbolism, evocative images and philosophical ideas in works as distinct as The Fountain (2006), Black Swan (2010) and Noah (2014). This time, with mother!, Aronofsky creates a stirring ecological allegory that seems to scream in absolute desperation as it begs us — humans — to stop acting like madmen bent on mindless destruction. It is a film that clearly wants to be the opposite of an enjoyable experience, which is why there will be so many people hating it and failing to get beneath its surface — like with the brilliant but criminally underrated Noah.

Audacious right from the first scene, mother! (with a lower-case m) begins with the striking sight of a woman engulfed in flames — notice the tear that falls from her eye — before we see “Him” (Javier Bardem) use a crystal to turn a burnt-out house into completely renovated. Then “mother” (Jennifer Lawrence) materializes in a bed and calls out for Him, her husband. Him is an author suffering from writer’s block while Mother, who looks much younger, is working to make a perfect home for their tranquil existence. But it doesn’t take long for things to change when two strangers, “man” (Ed Harris) and later his wife “woman” (Michelle Pfeiffer), arrive at their house followed soon by a horde of other uninvited guests.

Now, if I write “Him” (with a capital H), “mother,” “man” and “woman,” it is because this is how these characters are referred to in the end credits. In fact, no one is ever called by name in the entire film, which is only one indication (among many) of the film’s allegorical ambitions. The characters, as we soon realize, are archetypes — or symbolic representations of ideas that are impregnated in the collective unconscious of our Christianity-based Western culture. What Aronofsky wants is to create a strongly uncomfortable experience, forcing us viewers to share Mother’s growing stupefaction and feeling of violation as intruders invade her house without any respect for her personal space or herself as a woman.

In order to provoke this kind of emotional response in us, Aronofsky uses a nervous steadicam that never leaves Jennifer Lawrence’s side, filming her face in extreme close-ups and the other actors a bit farther away. This way, he keeps us in her shoes the entire time and in a constant state of apprehension, surprising us here and there with a few bumps in the dark almost like in a horror film. We begin to feel that not even her husband can be trusted, which is reinforced by the fact that he wears black the first time we see him. Adding to the mystery and a few surreal touches is a high-pitched whistling sound that is heard every time Mother feels sick before drinking a strange yellow liquid to calm her stomach.

The intelligent dialogue, on the other hand, conveys a lot between the lines, like when Mother asks Him if Man is “better” (not only as in feeling better but as in being better than her), or when Woman (played by a magnetic Michelle Pfeiffer) reassures Mother that “obviously” her husband “still” loves her. Isolated in her own house, Mother is, like I said, a symbol, which Lawrence embraces with full intensity while Bardem finds a perfect note of ambiguity for his character. With all this in mind, it is more than necessary now to analyze in details what mother! wants to say and how it does it, so the next paragraphs contain spoilers.

All over mother!, Aronofsky makes dozens of biblical references. The first “intruder,” Man, is sick and has a fresh wound on his back that clearly identifies him with the biblical first man Adam. Him tries to hide it so that Mother won’t find out that Woman — or Eve, made from Adam’s rib — is also coming. Woman, who is depicted as a vulgar creature full of vices and sexual desire, arrives right after and later tempts her husband to go with her into their host’s office and have a peek at the crystal — which, like the Tree of Life, is a source of divine creation. This leads to Him expelling the couple with a finger pointed to the room’s door just like God does to Adam and Eve, throwing them out of the Garden of Eden when the two eat from the forbidden fruit.

Then comes the blood, when the couple’s sons arrive and the “eldest son,” that is, Cain (Domhnall Gleeson), kills the “younger brother,” or Abel, (Brian Gleeson), triggering a chain of events that will lead all to chaos. The blood eats through the floor like acid, revealing a secret door in the cellar that Mother didn’t even know existed. Framed with blood, it is a literal door to destruction. It doesn’t matter how she tries to cover the hole on the floor and makes a baby’s room in the same chamber after finding out she is pregnant, soon the blood resurfaces, staining the carpet when people return to disturb her peace. All these elements are metaphorical representations of the birth of human violence in the world, contaminating what should be a nurturing home.

And that is what Mother is supposed to be after all, the female personification of nature — Gaia, Terra, Mother Earth, or mother goddess. Meek, passive and confused, she begs everyone to stop destroying her house but they don’t care. No one respects her. They thank their host (singular) and complain that she should “put on something decent” for the wake. Some men overtly insult her with sexist lines that end up creating an interesting parallel between the abuse of nature and misogyny. It is not by chance, in fact, that the film’s title is written with a lower-case m, since this also illustrates how small we think of Earth and the disproportional importance that people give to God, whose comfort they desperately seek in grief.

God is depicted exactly like in the Old Testament: absent when you need him (every time Mother turns to Him he is gone), selfish (not caring at all about her torment), and tremendously narcissistic, with a huge desire to be loved and admired. In one scene, Mother looks up and sees Him, almighty, framed from a very low angle and with light over his head. But more beautiful is how he enjoys the fact that people read his work in different ways — and so, when all war breaks out and they start killing each other, nothing is more natural after all than his publisher, or “herald” (Kristen Wiig), being the first to order Mother’s death, representing those who interpret the scriptures the way they want and use them as weapons of murder and destruction.

Religious cults quickly emerge in different rooms of worship, as well as fences that separate and isolate people — a fitting nod to Donald Trump and his border wall. But Him doesn’t want the intruders to leave; he wants to offer his newborn son to them. They are waiting, and when the baby is finally taken away from Mother’s bosom, it is killed by the mob and the insane father decides to forgive. Now, isn’t this exactly what the God of the New Testament does when his son Jesus Christ is murdered? A high priest says the child’s death doesn’t matter, for “his voice can be heard,” so I guess the devouring of the baby’s flesh shouldn’t be that shocking for all the faithful who consume the sacramental bread and wine in the Catholic Mass, right?

But if anyone is still uncertain about the film’s intended message, all doubts should evaporate in the end when Mother blows up the house. Unscathed by the fire, Him carries Mother’s burnt body and she asks him “what are you?,” to which he answers: “Me? I am I. You? You are home.” That is what she is, home, and the heart she felt beating when she placed her hands on the wall was her own heart, blackening and rotting as people destroyed the love that Earth represents in its capacity to generate life. But Him, or God, cannot recreate Paradise without love, so he needs to rape Mother one last time by tearing her heart out of her chest with his bare hands and using what is left of it to make a new crystal and start this sick cycle all over again.

In this scene, if you pay attention, you can see the glowing embers in the wood forming red and blue crosses behind them in the back. Although ignored and disrespected by man and religion, Nature is what keeps this world alive and people are relentlessly devastating it, now at a much greater pace than ever before. When Mother screams hysterically and begins to stab people with a broken glass at a certain point, it is like the hurricanes and earthquakes that come up without warning and make us curse the planet for what we do to it, raping it incessantly. As stated in the song that plays in the end, it is “the end of the world if you don’t love” your world anymore. So if Nature screams at the top of her lungs, perhaps we should listen.