Ciro Guerra creates a powerful film of transcendent beauty about the arrogance of the Western white man in relation to Native American cultures

Embrace of the Serpent (El Abrazo de la Serpiente) (2015)

Directed by Ciro Guerra. Written by Ciro Guerra and Jacques Toulemonde Vidal. Starring Nilbio Torres, Antonio Bolívar, Jan Bijvoet, Brionne Davis, Luigi Sciamanna and Yauenkü Migue.

Embrace of the Serpent, first Colombian film to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, is a film of transcendent beauty and splendor. Inspired by the travel diaries of German explorer Theodor Kock-Grünberg and American biologist Richard Evans Schultes, it takes us on a mythic journey into the heart of the infinite Amazonian jungle that has driven many to “complete and irremediable insanity,” exposing in the process the arrogance of the white man who conquers and destroys what is sacred to others. Even today it is possible to see the nefarious consequences of what has been done for centuries to entire Amerindian populations in the name of greed and cruel oppression.

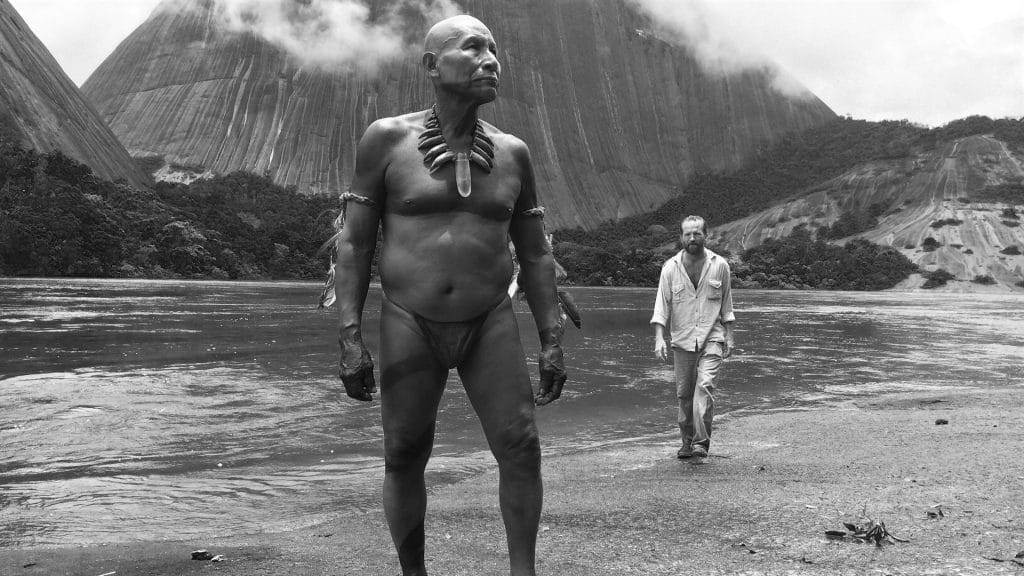

Written by Ciro Guerra and Jacques Toulemonde Vidal, Embrace of the Serpent is structured like a road movie (or a “river movie”) following two parallel stories thirty years apart. In 1909, German ethnographer Theo von Martius (Jan Bijvoet), who has been living in the Amazon for many years, is very ill and pleads with Amazonian shaman Karamakate (Nilbio Torres) to help him find a rare (fictional) sacred plant called yakruna that could save him. Meanwhile, in 1940, American botanist Evan (Brionne Davis) locates a much older Karamakate (Antonio Bolívar) in the hopes that he will help him complete the quest that Theo started so many years before — which Karamakate accepts for reasons we will understand only later.

Shot in a stunning black and white, with a 2.35:1 aspect ratio and usually in deep focus, Guerra’s film is a fully immersive and evocative experience. The magnificent cinematography explores the majesty of the jungle to such an extent that we are able to feel how someone might get lost in its mysteries, with each shot so beautiful it could be framed and put on a wall of any museum. The film’s sound design helps enhance that immersive feeling, almost placing us there alongside the characters on their journey, and Guerra also includes powerful images that seem like the very definition of visual mystic poetry, such as a jaguar killing a boa or the psychedelic explosion of shapes and colors that we see in a defining scene in the end.

It is an intensely mystic journey into the heart of the jungle, and that is reflected on moments like when Karamakate speaks of dream visions and prophetic messages from Master Caapi (that is, provoked by the hallucinogenic plant Banisteriopsis Caapi, commonly known as ayahuasca) or when he tells Evan that he has become a chullachaqui, a mythical lost soul that wanders through the world as a shadow of himself. This whole mysticism is intrinsically related to Karamakate’s life, as he believes that nature has something like a mind or a conscience of its own (at one point he says that “the river can tell you when to row”) and gods that protect it — gods that will punish us if we don’t respect the forest and the creatures living there.

And that brings us to the main theme in Embrace of the Serpent: the destruction promoted by the greedy white man who doesn’t value nature. Manduca (Yauenkü Migue), Theo’s travel companion, is an Amazonian Indian that Theo saved from enslavement on a rubber plantation (where rubber barons gave him back scars). The rubber barons enslave the natives and force them to extract latex from the seringueiras for use in rubber production. If they fail to collect sufficient latex, they are severely punished or killed. Many atrocities have been committed against Amazon Indians during those times, and today it is reported that thousands have been cruelly murdered. As Karamakate puts it, “If those rubber barons are men, I am a snake.”

But exploitation is not the sole horror they find along their way. In another moment, they come across a Capuchin religious order whose mission is to catechize natives in the hopes of eliminating their culture and language (which the priest in charge of the place calls “languages of the devil”). They steal boys from their villages “to keep them from cannibalism and ignorance” and impose their Western Christian values (which they believe to be superior) onto those who they consider “primitive savages.” It is infuriating to think that these things actually happened and helped erase entire Amerindian cultures, giving natives the only choice between slavery, death or the relinquishing of their ways of life by force.

But the white man’s arrogance is not only an active thing. Theo fights with a tribe of Indians over a compass because he wants to preserve the locals’ knowledge (Their orientation system is based on the winds and positions of the stars; if they start using a compass, their knowledge will be lost.) What he doesn’t realize is that, as Karamakate puts it, “knowledge belongs to all men,” and it is incredibly arrogant from him (if well-intentioned, though) to keep the natives in the dark to protect their primitive knowledge. Theo is not aware of his condescension, like an arrogant scientist probing into the wildlife using a microscope, while Evan, on the other hand, impatiently disdains Karamakate’s mystic beliefs as something without value.

Bijvoet and Davis translate superbly the scientific thinking that drives them to fascination or skepticism, yet the center of Embrace of the Serpent is definitely Karamakate in both his incarnations. When young, he is embodied by Torres as an angry man (but who can also laugh), skeptical of the white man and hoping to regain what he lost a long time before (his tribe), while when much older he is played by Bolívar as a regretful man facing an existential crisis (when Evan first sees him, Karamakate says “you can see me?”) It is only in the film’s third act that we understand what shaped the young Karamakate to become his older self and how he is trying to atone for a mistake that turned him into a chullachaqui of himself.

With a beautiful structure that connects the two plotlines so fluidly and organically, Embrace of the Serpent can be magical (the yakruna tree is entrancing in its supernatural beauty) or psychedelic (especially in the end). It can also be mad, like a scene (based on an actual event) that shows us a sect of Maku Indians worshiping a crazy “Messiah” who speaks Portuguese with a weird accent. Filmed in the Amazonía region of Colombia, the film is an essential look at an ugly past and a gorgeous piece of work that exalts the value of indigenous populations and their languages (Cubeo, Wanano, Tikuna and Uitoto), reminding us of the injustices that have been committed against them and that we should never forget.