Despite Gyllenhaal’s praiseworthy performance, Demolition is an unremarkable film that will hardly be remembered as one of Vallée’s finest works

Demolition (2015)

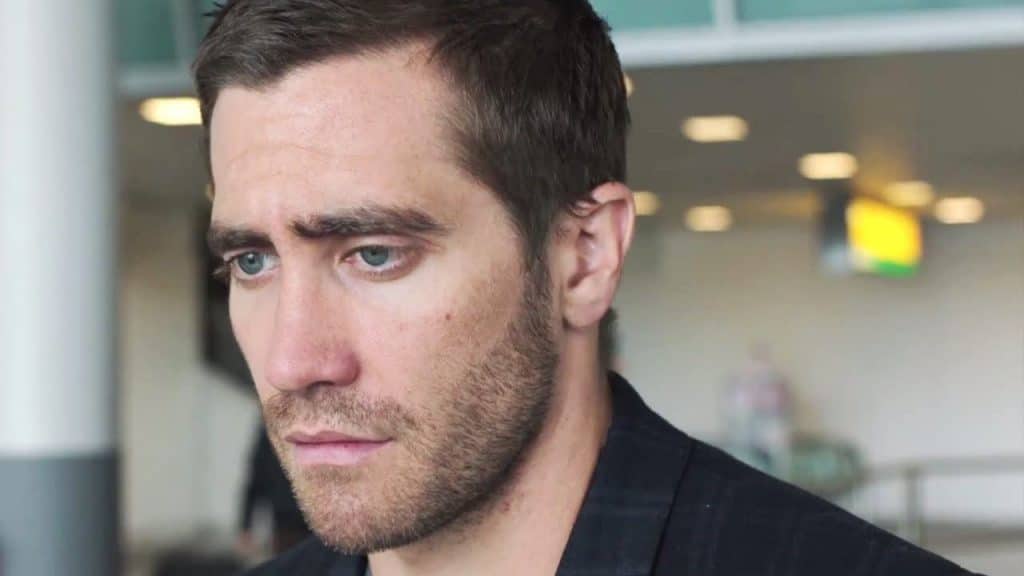

Directed by Jean-Marc Vallée. Written by Bryan Sipe. Starring Jake Gyllenhaal, Naomi Watts, Chris Cooper, Judah Lewis, Debra Monk and Heather Lind.

Jean-Marc Vallée is one director I admire. After his breakthrough with the exceptional C.R.A.Z.Y. (2005) in his native Québec, he went on to gain international recognition with the solid Dallas Buyers Club (2013) and the great Wild (2014) — both which meant Oscar nominations for Matthew McConaughey, Jared Leto, Reese Witherspoon and Laura Dern (with McConaughey and Leto taking home the award). Thus, it is a real pity to see Vallée follow those remarkable films with Demolition, which may not be a complete disaster (far from that) but will hardly be remembered as one of his finest works either.

Once again in charge of a film not scripted by himself (of all his works, he only wrote Café de Flore (2011) and co-wrote C.R.A.Z.Y.), Vallée makes us wonder why he took the job in the first place. Writer Bryan Sipe has never made anything relevant and Demolition feels more like an interlude in Vallée’s filmography before something better. Sipe’s schematic plot follows Davis (Jake Gyllenhaal), a phlegmatic investment banker who loses his wife in a car accident.

Incapable of crying or feeling any grief, his attention is deviated by an insignificant problem with a vending machine that prompts him to start writing complaint letters to the machine company. Soon, these letters begin to assume the character of personal confessions — an unsubtle but effective way of drowning us with exposition about his life — and they catch the attention of customer service rep Karen (Naomi Watts). The two form a strange connection, and, with her help and the help of her son Chris (Judah Lewis), Davis realizes that he must rebuild his life through the (metaphor alert!) demolition of his old one.

As anyone can imagine from the description above, this is a narrative based on metaphors like those that shaped Paulo Coelho’s career and made him a millionaire. But the film doesn’t bother to make that any subtle. In fact, it openly embraces those metaphors (the character even acknowledges their near-metaphysical existence around him), apparently believing that such recognition makes their use quirkier and clever. It doesn’t, and the way they are presented can be pretty obvious at times, like when we see a lamp switch on at a meaningful moment or when Davis has a panic attack and it seems that part of his heart is missing. Funny, but not an example of subtlety.

Regardless, it is a dramatic choice that fits well with the effective way it extracts humor from odd occurrences in the character’s life (like a mysterious station wagon that seems to follow him everywhere) and his bizarre apathy toward his wife’s death. Davis oscillates between a blasé attitude with regard to everything and a strange behavior that makes us sometimes think he is mentally deranged. This works for the best, because it gives him new layers as a character. If there is one thing that the movie usually does right, it is his characterization as a modern Mersault from Albert Camus’s The Stranger, judged and condemned by everyone for not behaving like “normal” people are expected to in human society.

Gyllenhaal deserves praise for the way he composes such a character. He is one of the best actors of his generation and deserved an Oscar for his performances in Prisoners (2013) and Nightcrawler (2014). In Demolition, he isn’t far behind. As he narrates the story of his life with a gripping eloquence in his letters (and shows us a lot about himself in the process), his character becomes fascinating with his eccentricities — from the suspenders he wears to his obsession with ripping things apart to see what they look like inside. Gyllenhaal manages to flesh him into a believable person, and I admire the film’s almost constant use of shallow focus to blur the background and emphasize his disconnection with the world.

And while Gyllenhaal only grows as an actor (and even becomes more physically attractive the older he gets), Naomi Watts continues in her disappointing path as a talented actress who now shows up in about three lame films for every The Impossible (2012) that stands out. Here, as in the mediocre St. Vincent (2014), she belongs in the narrative corner, playing a character who is more of a walking cliché than a real person. Chris Cooper, on the other hand, gets to offer another intense supporting performance (in a career full of them) as the increasingly exasperated father-in-law who cannot understand Davis’ way of dealing with his pain (which he naturally assumes he has).

To complete the cast, Judah Lewis displays a fine chemistry with Gyllenhaal that helps us get closer to their growing relationship and even laugh at the absurdity of seeing, for instance, Davis give a gun to a minor and ask him to shoot at him. Or when he gives the boy the most awful advice about his sexuality. As a character, Chris is a tough one to like at first, but later on, we get used to his presence and how he is supposed to be Davis’ metaphorical lever (like his mother) to literally break through his emotional stupor. And it can be quite enjoyable and funny to see the two interact as they try to help each other.

It is because the movie has so much potential that it feels so irritating (but not surprising) to see the kind of narrative tricks that it pulls off to appear more nuanced than it really is. They include an unnecessary, last-minute revelation in the third act (two, actually) and a gratuitous moment that shows, in parallel, two scenes of aggression that have no correlation with each other (not even thematic). Even though these missteps could have been left out, at least they don’t ruin the final result.

Punctuated by the songs Crazy on You by Heart and La Bohème by Charles Aznavour, Demolition may be too conventional in its structure but is charming enough in the way it tells its story. And for a movie whose main metaphorical message is basically “run forwards, not backwards,” it does deliver what it sets out to. It just won’t be remembered in the future as a great example of storytelling.